Chapter 11: toot that horn

“The ‘dumb’ Saxons got six answers correct out of 15

—the same number as those in the ‘brilliant’ group using the other book.”

John on his testing program in 20 Oklahoma schools, 1981

One of the most frustrating talents that John Saxon possessed, often groaned about by the mathematics establishment in news stories, was his showmanship abilities and natural knack for getting attention. He could do it with students, parents, non-teachers, business people, and even teachers, principals, and administrators. He was doing what came naturally. He had always been a passionate person who was willing to share his enthusiasm for whatever interested him. So, of course, he would stand out in the mathematics education community. How many individuals, for example, can remember having a math teacher willing to look a bit silly by wearing various hats in class (with a red light and siren that went off when a student’s answer was wrong), a wide range of academic interests (foreign languages and ancient history), and real “real-world” experiences with mathematics outside of teaching the subject? Who else drove around in a car with a license plate that promoted “Algebra”? And how many would place a chair on a table in order to get a better view of the audience or class while talking to or with them?

John had received some unexpected and lucky (or ordained) breaks in his life, such as surviving four airplane crashes, but he had also created some lucky breaks for himself with no-fear moves. One such event was his deciding to set up the Oklahoma field test. He was positive he would get great results. Just nine days before his National Review article was to be published on May 29, 1981, he received a copy of the official press release in which Mike Barlow of the Oklahoma AFT regaled the success of the testing program for his Algebra I book.1

Today the Oklahoma Federation of Teachers, AFT, AFL-CIO, released partial results of a project that herald a momentus breakthrough in the teaching of algebra in American schools. The scores of the test students were twice as high as the students who had the same teacher but were taught in the conventional method. The project was a massive test program conducted in 20 Oklahoma schools and involved 1365 Oklahoma Algebra I students. The schools were the public schools in the following Oklahoma towns: Carnegie, Cushing, Del City, Holdenville, Lexington, Lindsay, Madill, Marlow, Moore, Oklahoma City, Okemah, Okmulgee, Ponca City, Purcell, Seminole, Stillwater, Tecumseh, Wetumka, and Yukon.

The Oklahoma Federation of Teachers has monitored the program since it began in August 1980 and now certifies that the results are accurate. Sixteen tests on 16 basic skills were given to the more than 1300 students between February and May of this year. The data reduction on the first four tests has been checked, and the difference in the scores of the students in the test group and the scores of the control group students is amazing. On the 10-question test about evaluation, the test group outscored the control group by 64%. On a 15-question test about positive and negative numbers, the test group outscored the control group by 109%. They scored higher by 108% on a 10-question test about adding like terms; and, almost unbelievably, the test group students outscored the control group students by a whopping 141% on a 10-question test on solving equations that contain one variable. The test questions were selected from questions submitted by the teachers.

The same teachers taught both groups, and the control group students used the Algebra I textbook used last year by that school. The difference was that the test group used a prototype of a new book written by John Saxon, who teaches mathematics at Oscar Rose Junior College in Midwest City, Oklahoma. This book uses an incremental, continuous development—a startlingly effective innovation for writing mathematics books...

The next day, local newspapers started printing stories based on the AFT press release. In one of those stories, Roger Epperly, principal of Del Crest Junior High School, which had been one of the Saxon test schools, was quoted as saying he planned to use the Saxon book the following school year even though he couldn’t use [state] money to buy the book because it would not yet be on the state’s approved list.2 He explained that his school’s four classes of algebra had students assigned to them randomly by computer and were not assigned according to ability, which was the same way the classes were during the Saxon test program. To him, that meant the Saxon book was designed to meet all levels of students, even if they were in the same room. If John had set it up on purpose, he couldn’t have obtained a better testimonial for his new Algebra 1 book.

Mickey Yarberry, a Del Crest recalcitrant teacher who became a big believer in Saxon’s book, was quoted in a newspaper admitting she tried Saxon’s program only because she was desperate for something that would work for her algebra students.3 She still didn’t believe a book was that important because she had always been led to believe that a good teacher could do whatever was necessary to make up the differences between a curriculum and her students’ academic needs. So, she set out to prove to Saxon that a book wasn’t a major ingredient in the classroom. “I thought a good teacher could take up the slack, fill the holes, and do all else that was required to make up for the differences in books. How wrong I was,” she said.

After seven years of teaching, Ms. Yarberry had finished every year with a feeling of frustration. “I did not know the blame was not mine,” she said, until after her eighth year, which was spent with Saxon in one of her classrooms. She said she was sending her students to the next grade level who were well prepared, who could do their fundamentals, word problems, difficult percent problems, solve equations, and—most importantly—were content with themselves and happy with algebra. She finalized her praise by saying the Saxon book was one the students could read and which needed only encouragement and guidance from the teacher—“a lot of carrot and almost no stick.”

Ms. Yarberry then wrote in the Oklahoma School Board Journal that her students had been given time to practice, assimilate and time to digest the lessons.4 “They were no longer concerned with the mechanics of the problems. They were playing with the nuances. It was mind-boggling to see what they could learn from a book that was patient and gentle.” She said the brilliant became masters and the less gifted became skilled apprentices. “How different from the other classes where the brilliant were frustrated beginners and the less gifted were humiliated,” she said.

Principal Epperly then published his own article of praise in the National Association of Secondary School Principals’ Bulletin that fall.5 This would prove to be a major plan by which John would ultimately promote his program—through testimonials of those who had actually used the books and who were eager to tell the stories of their successes. He would list their names and addresses in his advertisements and encourage interested parties to contact them directly.

Other bold moves took place when he wrote to magazines asking them to follow his field test and report on its results. Only William F. Buckley, Jr., showed an interest in the field test and agreed to let him write an article about it. John figured, but this time wrongly, that an article in Mr. Buckley’s magazine would cause people to come running to his door with enthusiastic interest.6

The National Review magazine did indeed give John a large audience, but it was primarily of political conservatives.7 While it caused immediate critical responses from a few, there was a total shunning by most in the education community. This was for several reasons. First, he was not a member of the mathematics establishment circle. That is, he lacked the prerequisite and accepted credentials to offer any professional views about the math education field. Second, the general education community had long been associated with the liberal or Democrat side of politics in both their actions (financial donations) and words. His publication in a conservative magazine immediately established him as a political outsider, even though he had sought interest from magazines across the political spectrum.

The pattern of dismissing John Saxon as a “mathematics teacher” had begun. It was a pattern of behavior that he would confront and denounce for the next 15 years.

John opened his National Review article with this mantra: “Algebra is not difficult. Algebra is only different. And time is required for things that are different to metamorphose into those things that are familiar.” He then launched into a blistering attack on attempts to adapt “spiral” learning to mathematics and a new “fallacious theory” called mastery learning. The spiral procedure, he said, only involved periodic reviews of concepts, usually at the end of a chapter or unit. He said the distance from when students were first taught a concept and when they reviewed it made “spiral learning” ineffective.

Mastery learning meant a student took a unit test repeatedly until he passed it, then he or she went onto another unit, doing the same thing again, if necessary, while never reviewing what was in the previous unit until the end of the semester or year. “Only the brilliant can truly rise above such methods,” John maintained. “Mastery learning and spirals might be applicable to some subjects but not to algebra.”8 (He would later temper his opposition to the mastery learning idea after talking with its creator, Dr. Benjamin Bloom.)

John then described the unbelievable results obtained in his field test. He explained how the students had to be similar in demographics and skills and they were to be categorized within the classes as low performing, low-medium, high-medium, and high-performing prior to the study. Teachers had to have two classes of these students, with one class using Saxon and the other using the standard textbook.

A stunning outcome occurred when those in the low category of the Saxon group got the same number of correct answers as those in the high category in the other textbook on signed (positive and negative) numbers. He joked, “The ‘dumb’ Saxons got six answers correct out of 15—the same number as those in the ‘brilliant’ group.”9 He showed that those who used his book had scores more than double those in the standard textbook.

John said his field test proved that teachers were not to blame for students’ not learning mathematics. They simply needed adequate teaching tools. “The real culprits are the self-appointed standard-bearers of the new mathematics, who, with arrogant ineptness, have written the books from which the teachers have been forced to teach for 20 years. They brought with them an aura of omniscience and righteousness that placed them above criticism by people whose only attributes were brains, education, and common sense.”

He reported that the [standard] books confused and frightened students “by belaboring concepts that are trivial and by giving insufficient emphasis to concepts that are fundamental.” He said the word problems were either too difficult or were poorly written and problems requiring several different thought patterns were presented at one time and then snatched away “before even one type can be understood. These problems instill in many students a fear of word problems which is never dispelled.”

John expressed a concern about the impact that poor algebra teaching had on minority and disadvantaged students. He addressed the problem under the subtitle, “The Most Wounded.” He said, “Ask your local high school science teachers to detail their struggle to teach meaningful scientific concepts to students who are algebraically unprepared. This almost complete denial of knowledge of Algebra I is especially harmful to minorities and disadvantaged students because many of them lack the verbal and game-playing skills necessary to catch up later…By February of their freshman year, inadequate textbooks have crippled these students for life. They have been weeded out and will never be doctors, dentists, engineers, or physicists, nor will they ever do anything else that requires the knowledge that they have been denied.”

He also decried what he saw as a clear attempt to keep parents outside of the teaching process and the role that mathematicians had played in the growing problem: “The first time a seventh-grader brought home a mathematics book that his college-graduate father could not decipher, he should have raised unmitigated hell. Instead, we have all let these well-meaning pseudo-theoretical mathematicians convince us that they were teaching the students great thoughts that we, as adults, were not smart enough to understand. This was to be a matter between the teacher (who also did not understand), the child, and those who had written the books—parents definitely not welcome. Also culpable are our competent theoretical mathematicians who have stood idly by and watched without protest as this fiasco came to full bloom. Shades of Alice in Wonderland and New Clothes for the Emperor! We have let this go on for 20 years!”

John spoke of how the U.S. Department of Education had refused to help him on this project and that his overtures were rejected by six of the largest textbook companies because he was not “a committee of experts.” He then announced that his Algebra 1 book would be published in August 1981 by his newly created company, Grassdale Publishers.

Because of the fortunate support of the Oklahoma chapter of the American Federation of Teachers, John was being noticed throughout his home state. Because of the equally fortunate response by William Buckley, Jr., John Saxon was now on the national stage of mathematics education—whether the establishment folks liked it or not.

A criticism of John’s article appeared in the following issue of the National Review magazine.10 Mark R. Salser, a junior associate with Educational Research Associates in Portland, Oregon, condemned John’s attack on mastery learning. Given the chance to respond in the same issue, John used his well-honed love for vocabulary words and said, “Mr. Salser…proffers an ipsedixit from a Dr. Bloom which says that students using the mastery learning technique ‘should be capable of learning,’… Also, Mr. Salser says that mastery learning is one of the few practical philosophies to appear in the past two decades. Twenty years is a long time. Why do Dr. Bloom and Mr. Salser still suppose—where is their data? …Mr. Salser ignores concrete data and tells us what Dr. Bloom supposes would happen and suggests that the whole country should support Dr. Bloom. Then he accuses me of faulty reasoning… mastery learning students cannot pass comprehensive final examinations. My students can. Would Mr. Salser and Dr. Bloom care to wager? I would be happy to take their money!”

This would be one of the many shots fired at John for not understanding what it meant to be a full-fledged member of the “education community.” If he were a real teacher, he would have been a firm believer in Dr. Benjamin Bloom, an icon in teacher certification programs where “Bloom’s Taxonomy” and “mastery learning” were required studies. 11

John would later meet Dr. Bloom in 1988. He videotaped the congenial 45-minute session in which the icon said that John’s incremental learning program was actually supported by his own work on mastery learning, automaticity, and one-on-one instruction.12 John subsequently offered in his advertisements the opportunity for anyone to receive one of 300 copies he had made of the video. This behavior would become another egregious habit of John, as far as his opponents were concerned: When attacked, John always came back with irrefutable data or results to prove his point.

The cherry topping for that year of 1981 came on Dec. 16, however, when a story about John’s program was given a page and a half in Time Magazine.13 While a lot of public school educators may not have read a conservative publication like National Review, they did read Time Magazine. John had made his presence known on both sides of the political fence now. His “noise” could not be ignored by the establishment elites. Even the title of the Time’s article reflected an impending wrestling match: “New Angle on Algebra—One Teacher Takes on the Establishment.” The opening two paragraphs by the author were even better:

“His features are austere and regular as a mathematical formula, his carriage as straight as the vertical axis in a Cartesian graph. Teacher John Saxon’s eyes are the one variable in the equation: they burn with a visionary gleam. His vision is simple: a future in which the basics of algebra, the building blocks of all higher mathematics, become understandable to all American students.

“Saxon, 58, is an unlikely mathematical messiah. He still resembles what he once was: a professional soldier. A graduate of West Point, he is a World War II veteran, a decorated Korean War combat pilot and a former engineering instructor at the U.S. Air Force Academy.”

Publisher Bob Worth called, exclaiming, “John! You did it! You got in Time Magazine! And you got one and a half pages!”14 (He was also pleased that his name and company were mentioned in the article.)

The leap onto Time’s pages was from pure John Saxon bravado. He had talked with Jean Marie North, a researcher for Time, after his second article was published by National Review in October of 1981. He offered to send Ms. North copies of his two articles and results from the Oklahoma tests. Three days after mailing them, he called her again. He said he would be coming to New York City during the Thanksgiving holidays; she said he could drop by her office to answer some questions if he were available. When he got off the phone, he called for airplane reservations.

Selby remembers this incident vividly because she had called to wish her daddy a Happy Thanksgiving only to learn from Johnny that their father was in New York City to talk with Time Magazine. She asked if they had called him for a meeting. “No, he’s just going up there and knocking on their door,” he said. “On Thanksgiving weekend?” she asked, incredulously. “No one will be there!”

However, their father had laid out better plans than anyone knew. He ended up talking with the education editors for a couple of hours and 11 days after Thanksgiving, his story was in the magazine. Selby concluded that everything her father touched had finally turned to gold simply because he was not afraid to knock on doors—and many of them had started opening.

With those test results in hand, the AFT press release, two of his own articles in a national magazine, and now a human interest story on him in another leading national magazine, John knew it was time to start buying advertising space in the education journals. Unlike his competitors, John also knew there would be great value in continuing to write for the general public—especially, he said, to those “mommas and daddies” who wanted their children to learn mathematics.

His first national advertisement was published in Mathematics Teacher magazine in December, 1981.15 As a teacher, he had joined the organization that published that magazine, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM). He knew well their philosophy of teaching mathematics by this time and knew it was diametrically opposed to his. By choosing to pay for full-page advertisements every month in their own magazine over the next 15 years with messages that attacked their methods and beliefs, John had chosen to insert himself into the heart of an organization that was known for its authority and political clout in Washington, D.C.

After a few months, the magazine’s directors refused to accept his ads until they had established a new “advertising policy.”16 He said he pouted for awhile and then submitted an editorial and asked that it be run as an advertisement. That request was approved.

So, he wrote wall-to-wall copy in most submissions, often using brash, sensationalized wording and all-capitalized titles in bold font. He never had color or pictures in his “ads,” although there were a few with line graphics in later years. His stark but gray pages from black print on white paper were a major departure from the normal soft-sell, full-color advertisements that offered soothing and happy-oriented come-ons to potential customers. His said things like the following:

…‘REAL WORLD PROBLEMS’ ARE THE CAUSE, NOT THE CURE, May 1983

…MINORITIES DON’T SEEM TO BE IMPORTANT IN TEXAS, December 1983

…HOLOCAUST IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION—A FAILURE TO CONCENTRATE ON

FUNDAMENTALS, January 1984

…HELP HELP HELP HELP, December 1985 (calling for information from those using Saxon)

…WHY THE DISASTER IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION WILL CONTINUE, 1987

…TERROR AT 3000 FEET, November 1991

…MY SMILE IS A WRY SMILE, December 1994

Every now and then, he would offer a more vanilla title. When his beloved Calculus book was published in 1988, for example, all the advertisement said was, “A New Calculus Book.”17 In the opening, he noted that this book “by John Saxon and Frank Wang…is different because the authors accept the fact that understanding the abstractions of calculus does not occur on the initial encounter, no matter how brilliant the presentation.” After describing the book’s contents, John closed by writing in bold font,” The book is different, different, different and it works, works, works. Try it. You’ll be amazed at the results.” (his emphasis)

His common theme was to challenge those who weren’t using his books or those who offered generic criticisms of his program. In October 1989, his ad asked, “What’s your excuse for not piloting Saxon Math this fall?” Then he had subtitles of “My gifted students would be bored”; “It just wouldn’t work for the average student”; and “How could I expect my lower-ability students to do 30 problems a night?” Under each statement, John printed testimonials from teachers to counter these concerns.18

He especially enjoyed challenging those who criticized his program for not preparing students to “think.” In a 1991 ad, “AP Calculus Scores Rocket,” he chortled, “When increases of 20-50 percent on standardized test scores were announced, the scoffers said, ‘He makes up his own tests and test results don’t count. We want to teach students to think.’ Now we will have many students completing 13 semester hours of engineering calculus in high school. These students can’t think? The students have climbed this high by using blind, mindless drill? We don’t think so!”19

In the 1982 spring issue of American Educator magazine, published by the American Federation of Teachers, a writer had said, “Saxon’s contempt for standard mathematics texts has earned him criticism, but he is unrepentant… ‘This is not debatable.’ Then he quoted John: ‘It works. We doubled and tripled the scores. Just as a football or basketball coach cannot teach the nuances of the game without practice, practice, practice, so you cannot master algebra without practice. When they prepare for a game, they don’t practice esoterica; they practice their fundamentals.’”20

The constant accusation by the establishment became that Saxon books were “It’s drill and kill.” John would ultimately spend hours and print space trying to get people, including the elites, to understand the difference between drill and practice.

In July of that year, Mr. Buckley’s nationally syndicated newspaper column was printed with the headline, “John Saxon: the Rickover of Algebra.”21 He wrote, “John Saxon…will probably figure as prominently in the history of mathematical pedagogy as Hyman Rickover in the history of the development of nuclear submarines… The two gentlemen are temperamental clones. If it ever occurred to Hyman Rickover that he was wrong about anything, one must assume he lay down until he got over it. It is so with John Saxon…who…took up the teaching of algebra.”

Mr. Buckley reported that John was shocked to find himself surrounded by a generation of algebraic illiterates, “and anyone who shocks John Saxon should be prepared to take the consequences.” Americans had not lost their basic mechanical intelligence, Mr. Buckley wrote, “which we like to think of as congenital.” He went on to explain how the panic of 1957 and Russia’s launching the first space satellite had caused President [Dwight] Eisenhower to initiate a crash program “designed to hype American interest and skill in engineering.” These are the individuals who created a set of textbooks “blighted by jargon (Saxon’s is a model of precision), indifferent to practice, and rather snobbish about utility.”

Mr.Buckley then said that an Armageddon is taking place among the mathematics establishment as John’s story is being heard and retold across the country.

A few weeks after this column appeared, the Oklahoma City school system decided to junk all the algebra textbooks—in favor of the Saxon text.22 A copy of Mr. Buckley’s column was also clipped and sent to John by a gentleman named Gary Rundle, O.D., with the following message attached: “Dear Mr. Saxon, If you’ve not registered your book with Texas for consideration, please do so…Algebra comes up for consideration March 1983 for the year 1984-85. I applaud your efforts!”23

Mr. Buckley’s column also prompted letters to the editors of newspapers. Mary Parker was with the mathematics department of Austin (Texas) Community College and said they had used John’s book in the elementary algebra course for a year. “Not only do the ‘good students’ like it and do well with it,” she said, “but the students with poorer backgrounds and those who are afraid of math and slower at learning math find they can learn the material well with a minimal amount of frustration.”24

Dr. Janet Catlin, a teacher in the Humanities Department at Oscar Rose Junior College, wrote how she had consulted with John when her 13-year-old daughter, who was on a fast track math course at her Norman middle school, was having problems and her teacher had recommended that she repeat the course [during 1982-83]. John suggested her daughter work through the Algebra 1 book during the summer. “She did so, consulting him by telephone whenever she got stuck,” said the mother. Dr. Catlin said her daughter’s attitude turned around with his enthusiastic assurances and lucid explanations that convinced her she “could do it.” Without much effort, her daughter was making straight A’s in pre-algebra and had not needed to repeat the course.25

John was getting the attention of those “mommas and daddies” whom he wanted in the children’s education.

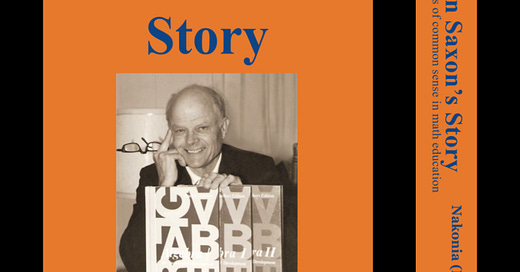

Hundreds of articles were printed about him, often the same wire story being carried in major newspapers across the country: “John Saxon’s blue eyes flash with visionary zeal…” was the lead paragraph in September 1982 in at least 17 newspapers from California, Montana, Ohio, and Georgia.26 A picture usually showed him holding his book in crossed arms, head lowered and looking intently over reading glasses, with a rather impish grin on his face. He was having a ball by all media accounts.

Editors learned that while John had an extensive and often rarified use of a rich vocabulary that was sometimes inserted in his stories and advertisements, he could still write “lucidly” (as Mr. Buckley had described it) for the general public’s understanding. This was proven with his National Review articles.27 Once published at the national level, he did not find it difficult to get his articles printed in other national outlets. He also had a second article in National Review on Oct. 16, 1981, 28 and a third one on Aug. 19, 1983.29

Numerous guest columns and commentaries that he wrote appeared in the following October and November 1983 newspapers: The Christian Science Monitor 30; The Washington Post 31; Minneapolis Star and Tribune 32, and Tulsa World.33

He also maintained a correspondence with, now, “Bill” Buckley and managed to keep it succinct, compared to the long missiles of information that he delivered in advertisements. In 1986, for example, he wrote, “Dear Bill, I am distraught. In your National Review thank-you letter of April 3, 1986, you promised me a ‘modest token’ of your thanks. In past years you gave me an ‘exiguous token.’ This helped me to learn the difference between exiguous and exigent, the word always used by the Air Force when they changed my orders to something less desirable. I did so want another exiguous token. Sounded like it should mean exotic, but when the token came I realized it meant something else. Sincerely, John”34 (In John’s scrapbooks was a neatly posted check from National Review for $300.)

Mr. Buckley responded, “Dear John: I have told you before, that although you are revolutionizing the teaching of algebra in the public schools, you really should turn to the problem of illiteracy. Cordially, Bill”35

Richard Brookhiser of National Review then wrote a story in December 1983 under the title, “What Makes Saxon Run?”36 He quoted John as saying, “I had decided before the course began [after his first semester at Oscar Rose Junior College], I’m going to th’ow out all theory. I’m just going to shotgun it. Whatever works—I don’t care.” Describing John as a man who looked like John Glenn and “speaks like a good ol’ boy,” Brookhiser said John was “a teller of his tale as a struggling teacher and is not above playing the Dumb Rustic or below speaking with an evangelist’s tongue.”

A review of his field testing and a subsequent study at the University of Arkansas was given with testimonials by various users of John’s Algebra I book in the article. When asked why other books hadn’t done it this way before, John had told Mr. Brookhiser, “Because other textbooks were written by pedagogical spastics.” The author ended by saying that John’s message was longer on hope than indignation. He said John insisted, “There’s nothing wrong with students or teachers. If students get enough practice, they can learn.”

More excitement came with a story in 1985 by Trevor Armbrister of Reader’s Digest Magazine.37 He had even traveled to Norman to visit with John. He wrote how John’s books were being used in prestigious private schools such as Kent School in Connecticutt, Deerfield Academy in Massachusetts, and Georgetown Day School in Washington, D.C., “but Barbara Stross in Portland, Oregon, is most impressed with what Saxon’s book does for many poor students.” While this article told of John’s beginnings with his Oscar Rose Junior College students and the Oklahoma field testing, it also told of some opponents’ views.

Such stories and letters became standard fare, reaching almost a crescendo of applause for the Saxon program, especially as John became more known through interviews, attendance at conferences, or as a guest speaker at meetings. He clearly enjoyed every opportunity to talk with anyone who would listen to his story. He was seen as bigger than life—a former combat pilot yet down-to-earth in his understanding of the struggles of most American students and teachers in mathematics. He could rattle off data from the schools using his book which allowed interested persons to check his facts. Assigning him descriptive names like “the Ross Perot of mathematics education”38 and “the angry man of mathematics education”39, reporters did what they normally do by labeling a person through one or two of his actions or physical appearances. John was being given persona that would both precede and follow him. He seemed to thrive in such a demanding atmosphere and didn’t mind what was being said—unless there were factual errors made in a story or a letter to an editor. When that happened, he was quick to send a challenge to those reporters or letter writers, chastising them for printing incorrect information.

A particular bigger-than-life moment for John himself came in July 1983 when he learned that President Ronald Reagan had given his book a plug at a White House reception for 220 elementary and high school principals.40 President Reagan had exhorted the educators to join in his crusade for higher standards in public schools and to look for ways of improving standards that didn’t increase costs for education. “If a 600 percent increase…in the past 20 years couldn’t make America smarter,” he asked, “how much more do we need?” After making that remark, he told of John’s book, which he had heard about in a personal note from Allen H. Ryskind, editor-at-large for Human Events, a conservative weekly newspaper.41

President Reagan told the school administrators about the data from the Oklahoma test in which Algebra 1 students using John’s book scored above the Algebra 2 students who had used the traditional text. Saying that John’s books could do wonders with increasing math skills, the President said, “Here’s another area we could look into; all we’d have to do is simply replace the old books as they wear out with new books of this kind.”

Among many interviews and sound bites on television newscasts about textbook adoptions, John made an appearance on Dick Cavett’s show 42 and was in a video with Jaime Escalante, the subject of the movie Stand and Deliver and a fellow math teacher who had used John’s books on occasion.43 During that 1984 interview of 30 minutes, Mr. Escalante mainly listened as John answered questions. When John used football coaches Don Shula and Vince Lombardi as examples of those who insist that players go through the “fundamentals because they must be total masters of those fundamental skills,” Mr. Escalante leaned forward into the conversation and nodded his head. “But,” John added, “the present math books are unsure what the fundamental skills are.” Again, Mr. Escalante nodded in agreement. John continued, “Most kids are not interested in algebra but they are going to form the core of our society and we must be smarter than they and teach them as far as we can.” He insisted that teachers must concentrate on concepts, but “that doesn’t mean they can apply concepts in the real world before they can understand them.” Mr. Escalante nodded adamantly. When John said that a monkey could have come up with the reasoning that concepts should be taught by application, Mr. Escalante shifted forward in his chair in animation of agreement and inserted, “They don’t.”

Perhaps the most notable and beneficial television appearance was with Mike Wallace on 60 Minutes in 1990 as they talked about Saxon Math’s amazing results in the high-risk and predominantly minority North Dallas (Texas) High School.44 John felt the television show’s producers had come to prove that his program wasn’t as successful as he claimed but, instead, he learned that just the opposite came out during the show.

For example, the crew of 60 Minutes had brought in a group of individuals to express different views of John’s work. One woman attempted to berate him by saying, “We’re not trying to turn children into little machines that can operate the same way as an electronic calculator. That’s what your material is trying to do to kids.” Mr. Wallace then said to John, “Teachers are sharply divided. There are those who don’t like it at all.” The woman then continued to talk, not giving John a chance to respond. He finally said to her, “Let’s not get into a dogfight here, Ma’m; this is my session. Don’t come into my session to give me trouble.” The woman was not shown speaking again.

The 60 Minutes segment did partially answer a quest he had started in 1987 when he said he “ached to get investigated by the major media” for the chance to prove he had a better method for teaching mathematics.45 Actually, he had begun encouraging such investigations in 1983 with his article for National Review magazine in which he challenged the readers to “investigate my books. If I am a fraud, then I should be exposed; but if I speak the truth, then I deserve support.”46

John relished the chance to talk with anyone at any professional or personal level or age who had questions about his program. It also helped when they learned that he was still teaching his two classes at the junior college until 1985. He wasn’t speaking from academia’s “ivory tower.” For John, there was no talking down to parents, students, and teachers, as though they knew less than he did. They were, he said, the ones who had common sense on their side.

He set up booths in the countless NCTM regional and annual conferences through the years. In 1987 and 1988, for example, he manned an information booth at NCTM conferences in Virginia, Georgia, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Texas, and Illinois; then he did the same thing for the Association of Christian Schools International in Indiana, Colorado, Kansas, Texas, New York, West Virginia, and Massachusetts. Noticeably different from the other vendors, John rarely had “gifts” to hand out to those who dropped by his table, other than his business card. He finally agreed to distribute pencils and, at a later time, he did offer t-shirts.

John even kept some of the evaluation scores for his presentations. At the 1983 Omaha, Nebraska, NCTM conference, of 81 evaluations, he got 58 marked as excellent; 13 were good; eight, satisfactory; and two, not worthwhile. The importance of knowing the results and openly sharing that information was simply part of John’s value system. It reflected his accountability for his work.

Supporting his belief that mathematics education wasn’t just of interest to teachers but should be of vital interest to parents, he bought advertisements in general periodicals that explained his no-nonsense beliefs and that promoted his books. He had already started doing this in the Norman newspaper in 1980 as he worked to bring change to the math curriculum options within the school district. Other ads were now in The Daily Oklahoman, Human Events newspaper, and The American School Board Journal. When his book was being considered for adoption in those states that used textbook committees, John ran at least one-half page ads in major cities of those states directed at parents.

For most people that worked “wonderfully well,” in John’s words. For those who could not give firm data for their beliefs and who had built professional lives on the pedagogy of “feelings,” his approach was infuriating. They tried to talk down to him as someone who couldn’t possibly understand the “art of teaching.” This never worked because he would call their hand on it publicly and challenge them to prove their points. Since they couldn’t refute his data with any valid or reliable data of their own, they had begun to attack him personally. Most important, they knew that while they held the seats of power in the publishing arena and academia, they also had parlayed a major hand in local decision-making about curriculum—and that should help stop the spread of Saxon Mathematics.

In spite of his opponents’ real or perceived importance, John loved the art and skill of competition and was very good at pricking the thin skin of academic elites, whether it was simply a way to get their attention or to respond to any charges they made against him or his program. Aware of his dad’s aggressive approach to publicity for his books, his son Johnny asked him what he was trying to do with such actions. “I want every math class in America to talk about me,” he said.47 In addition, the “violent disapproval” of him among mathematics educators made him think that book companies wouldn’t copy what he had done. “If they give me three or four years, I’m going to have a big hunk of the market,” he said.48 That would bring him more money to spread his successful program and thus more power to be heard.

John’s most consistent public relations efforts were his advertisements in Mathematics Teacher Magazine. Excluding a handful of months in which the magazine’s advertising director refused to run his advertisements because she didn’t like some of his words, John published about 175 ads in that magazine for 15 years, until his death. Some issues had a double spread, or two pages, of his advertising. At an average of $1,000 per ad, John spent about $175,000 on those ads.

One of the complaints from the Mathematics Teacher’s advertising director was written about by John in his March 1989 double-page ad for that same magazine.49 He pointed out that he had originally reserved that space to reprint an article written by Dr. Chester A. Finn, Jr., which had been published in the Nov. 24, 1988, issue of the National Review Magazine. The ad manager rejected the reprint, he said, because it “violated their policy that…prohibits derogatory and inflammatory statements.”

John wrote in the replacement ad that Dr. Finn’s article did say, “The disaster in math education was caused, and the same people who caused it were preventing a recovery.” John declared he had also written previous ads that used good English words such as “specious, arrogant,” and “absurd” and they had been accepted. “Since no one seemed to be mad about the apparent disaster in math education, I set out to see if anything would make them mad.” He said that after two or three ads had been printed, the letters of outrage began pouring into the publishers of the magazine, and he had to start “euphemizing” to get future ads published. “Seems that no one was mad about 82 percent of our 17-year-olds not knowing what the word ‘area’ meant [on a 1983 international test], but my anger at this state of affairs caused great resentment. I was amazed.”

Then eight months later, in November 1989, the advertising manager notified John that she didn’t like his wording in another replacement ad he had planned for the January 1990 issue. He had created the new ad at the last moment based on the upcoming 60 Minutes television interview. If he wanted to run this replacement ad, he would have to change the following sentence: “Mr. Wallace has interviewed Saxon teachers and students as well as representatives of the math establishment.” She suggested, instead, that he write, “Mr. Wallace has interviewed Saxon…as well as others involved in mathematics education.” John had one week to make the change or use the original ad. He changed the wording because he didn’t think there was any real difference between the sentences.

In October 1995, his ad was once again refused again because it was considered too inflammatory. This time he didn’t budge. Entitled “Proposed Math-Testing Standards Damaging to Minorities,” John got it published that month, as written, in both Education Week and Teacher Magazine. Some other teacher-oriented publications in which John consistently advertised his thoughts—without any efforts to censor his writing—were Physics Teacher, American Mathematical Association, Today’s Catholic Teacher, National Independent School Teachers Association, National Association of Secondary School Principals, and Education Week.

“One of the things I do,” he said, “is I promote controversy. My ads say bluntly that they have been doing it all wrong and telling the big lie for 25 years.”

All of John’s actions and words were greatly appreciated, however, by reporters since a number one selling feature within the news business is “conflict.” While his words were often incendiary and certainly not the acceptable mode within a clique or community that prides itself in theory—if not in practice—on “playing nice in cooperative groups,” his words were painting an outsider’s picture of irresponsible actions and results within that community.

John had established a root-hold on his position as a successful mathematics teacher due to his program’s results, not its promises, within two short years of appearing on the national scene. Of special importance to him was that by October of 1982, he had sold enough books to buy back the $45,000 mortgage to his home. But the greatest importance was that he had repaid his children earlier that year for their loans to help him print that first Algebra I textbook.

Share this post